By the end of 2020, 399 offshore wind turbines will have been installed in the Belgian part of the North Sea. During the past decade, scientists have monitored their impact on the marine environment. For the occasion of Global Wind Day 2020, the scientific partners and the Belgian Offshore Platform summarize what we have learned so far about the longer-term effects onto a variety of ecosystem components, from seafloor invertebrates over fish to birds and marine mammals. The environmental impacts of offshore wind farms prove not to be black or white: turbine foundations do initiate diverse ‘reefs’ of seafloor invertebrates around the turbines but are no equivalent alternatives for species-rich natural hard substrates, wind farms attract some seabird species but deter others, piling sound impact on harbour porpoises exists but is short-lived, offshore wind farms locally benefit the fish fauna and do not influence fisheries in a negative way. These nuanced insights allow to further trigger mitigation of the unwanted impacts and to promote the impacts deemed good towards a maximum environment-friendly development of offshore wind farms.

Offshore Wind Energy in Belgium

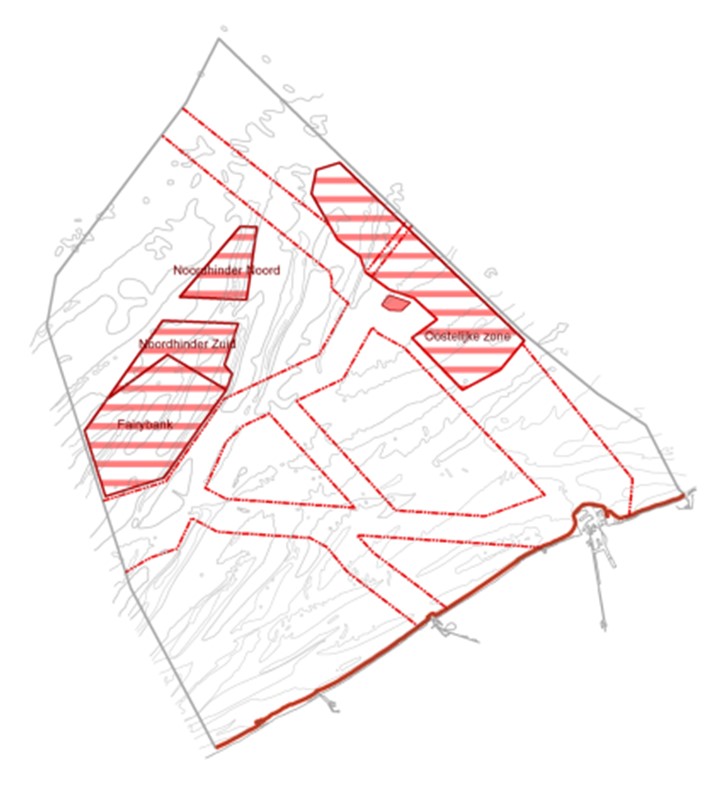

Belgium is a world leader in the offshore wind industry. In the ‘first offshore wind phase’, a zone of 238 km² was reserved for wind farm construction along the border with the Netherlands. From 2008 onwards, 341 wind turbines with a total production capacity of 1775 MW were constructed in this zone, grouped in seven wind farms. The six first wind farms have produced 4.6 TWh of electricity in 2019, representing about 6% of Belgium’s total electricity consumption. The seventh wind farm is operational since May 2020, and an eighth wind farm will begin to produce energy in the second half of 2020, bringing the total number of turbines to 399. The production capacity will then increase to 2262 MW and the production of an average of 8 TWh or approximately 10 % of Belgium’s total electricity demand. A second wind zone of 281 km² close to the French border (the ‘second offshore wind phase’) is established in the new Belgian Marine Spatial Plan for the period 2020-2026. This zone intends to add a minimum of 2,000 MW to the total Belgian offshore wind energy production capacity.

During the past decade of offshore wind farm construction, the technology and construction practices have changed drastically. Changes include an evolution in foundation types (from gravity-based and jacket foundations to XL monopile wind turbines), an expansion of the construction area towards more offshore waters and an increase in the size and capacity of the wind turbines (from 3 MW turbines with a 90 m rotor diameter to 9.5 MW turbines with a 164 m rotor diameter).

Monitoring Ecological Impact

As the installation of wind turbines at sea inevitably has a certain ecological impact, developers do not only need domain concessions but also an environmental permit. These are only issued if an assessment based on current insights shows that the impact of a wind farm on the marine environment is likely to be acceptable. They also impose a monitoring programme that assesses whether the predictions were accurate and whether certain environmental effects were overlooked or should become subject to adjusted environmental conditions.

Annemie Vermeylen, secretary-general of the Belgian Offshore Platform, the (non-profit) association of investors and owners of wind farms in the Belgian part of the North Sea, explains why and how the sector is involved: “The generation of wind energy at sea is part of the ongoing transition to the production of sustainable, green energy, which is widely supported by society. In order to be entitled to rightfully use the term ‘sustainable’, wind farm operators are contributing to the funding of scientific research on the impact of wind farms on the marine environment.”

The monitoring programme WinMon.BE has evaluated the environmental impact of both the construction and operational phases of the Belgian offshore wind farms from the start. “With this programme, we develop a proper understanding of the impact of the offshore wind industry on different scales. We learn to distinguish between shorter- and longer-term effects, and gain insight into the impact of individual wind turbines as well as of all wind farms combined“, says Steven Degraer of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, coordinator of WinMon.BE. “In order to understand the cumulative impact of wind farms in the southern North Sea we also need to look beyond our borders. For example, 344 km² are set apart for wind farm construction in the adjacent Dutch Borssele area, and 122 km² in the French Dunkerque zone, while marine fauna doesn’t know national borders” Degraer adds.

Effects are Diverse

As WinMon.BE evolved to be the basis for the understanding of effects of offshore wind farms on different spatial and temporal scales, onto a variety of ecosystem components (from seafloor invertebrates over fish to birds and marine mammals) and also on the seabed itself, it is difficult to summarise the impact as ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. The series of WinMon.BE reports describe all the results of ten years of monitoring of offshore wind farms in the Belgian part of the North Sea in detail. Main lessons learnt include:

- Impact is often specific to sites, foundation-types or even individual turbines

This highlights the importance of a continued monitoring at the different sites and turbine types.

- Foundations are not a long-term alternative for species-rich natural hard substrates

There are three succession stages in the fouling communities on wind turbine foundations. Earlier reports describing these as biodiversity hotspots generally refer to the species-rich second stage (characterized by large numbers of suspension feeders, such as the small amphipod crustacean Jassa herdmani), but continued monitoring now shows that a third, possibly climax stage follows. This has a lower species diversity, with frilled anemone and blue mussel as the dominant species.

- Foundations have a ‘reef effect’

Sediment fining and higher densities (biomass) and diversity (species richness) of seafloor communities (e.g. worms, shellfish, crustaceans and starfish) are consistently observed in closer vicinity of the wind turbines. Species associated with hard substrates also appear and increase in abundance in the surrounding soft sediments. Over time, the ‘reef effect’ of a single turbine may expand to the level of wind farms.

- Effects of wind farms can differ substantially between species within the same species group

Monitoring showed avoidance of the wind farm area by northern gannet, common guillemot and razorbill. In contrast, great cormorant, herring gull and greater black-backed gull are attracted to the wind farms. Apart from birds, it is also clear that differences in attraction exist among invertebrate and fish species.

- The direct sound impact from turbine installation is short-lived

The high impulsive sound levels produced during offshore wind farm construction (pile driving) result in displacement and disturbance of harbour porpoises, the most common cetacean in the southern North Sea. During pile driving, detections decrease in areas up to 20 km around the construction sites, but this is no longer the case once the wind turbines have been installed.

- New habitats attract some unexpected visitors

Some species that were only rarely observed in the Belgian part of the North Sea, are now more regularly found in association with the wind farms. These include at least four rock-loving species of fish that dwell around the base of the foundations, but also a number of non-indigenous invertebrates that occur in the zones near the water surface (intertidal and splash zones). The latter habitats are largely new to the offshore part of the Belgian North Sea. It was also demonstrated that the offshore wind farms are visited by migrating Nathusius’ pipistrelles, a species of bat.

- Fisheries are not negatively affected by the presence of the Belgian offshore wind farms

The exclusion of fisheries from the Belgian offshore wind farms, probably in combination with increased food availability near the turbines, leads to a refugium effect for some fish species. An analysis of the fishing activity and efficiency showed that fishing had only subtly changed over the years, and that fishermen have adapted to the new situation by increasing their fishing effort at the edges of the wind farms. Catch rates of sole remained comparable to those in the wider area, catch rates of plaice were even higher around some wind farms.

Mitigation Measures and Future Research

“The current cooperation model, in which the offshore wind industry and scientists document the impact of both the construction and operational phases, also allows us to design, test and improve mitigation measures to directly manage unwanted effects on the marine ecosystem” says Degraer. A selection of impact mitigation techniques is also presented in the WinMon.BE reports. An obvious example is the sound mitigation, e.g. by means of Big Bubble Curtains and acoustic deterrent devices, that mitigate the impact of impulsive sound on marine mammals and potentially also on other marine organisms. But mitigating solutions don’t necessarily have to be high tech, e.g. curtailing the activity of turbines when bird migration or bat activity is high, can lower the risk on collisions. Offshore wind farms, on the other hand, also offer great opportunities for strengthening positive impacts like the reef effect attracting fish and increasing biodiversity. This knowledge may be used to take action to further promote biodiversity inside wind farms.

Although our understanding of the effects of wind turbines on the marine environment and its inhabitants has grown significantly over the past 10 years, there is still much scope for future research. The modelling of bird and bat collision risks and the monitoring of the impact of continuous underwater sound that is generated by operational turbines are examples of fields that we have started to explore but cannot yet report on. Also what the longer-term effects on fish populations are, and how the observed behavioral changes impact individual fitness, reproductive success and survival of animals remains yet unknown. In addition, it is also important to further extend the time series of all variables that we have monitored to see if the patterns that we have seen so far are perpetuated.

The Monitoring Programme WinMon.BE is a cooperation between the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), the Research Institute Nature and Forest (INBO), the Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (ILVO) and the Marine Biology Research Group of Ghent University, and is coordinated by the Marine Ecology and Management team (MARECO) of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

Global Wind Day is a worldwide event that occurs annually on 15 June. It is a day for discovering wind energy, its power and the possibilities it holds to reshape our energy systems, decarbonise our economies and boost jobs and growth.