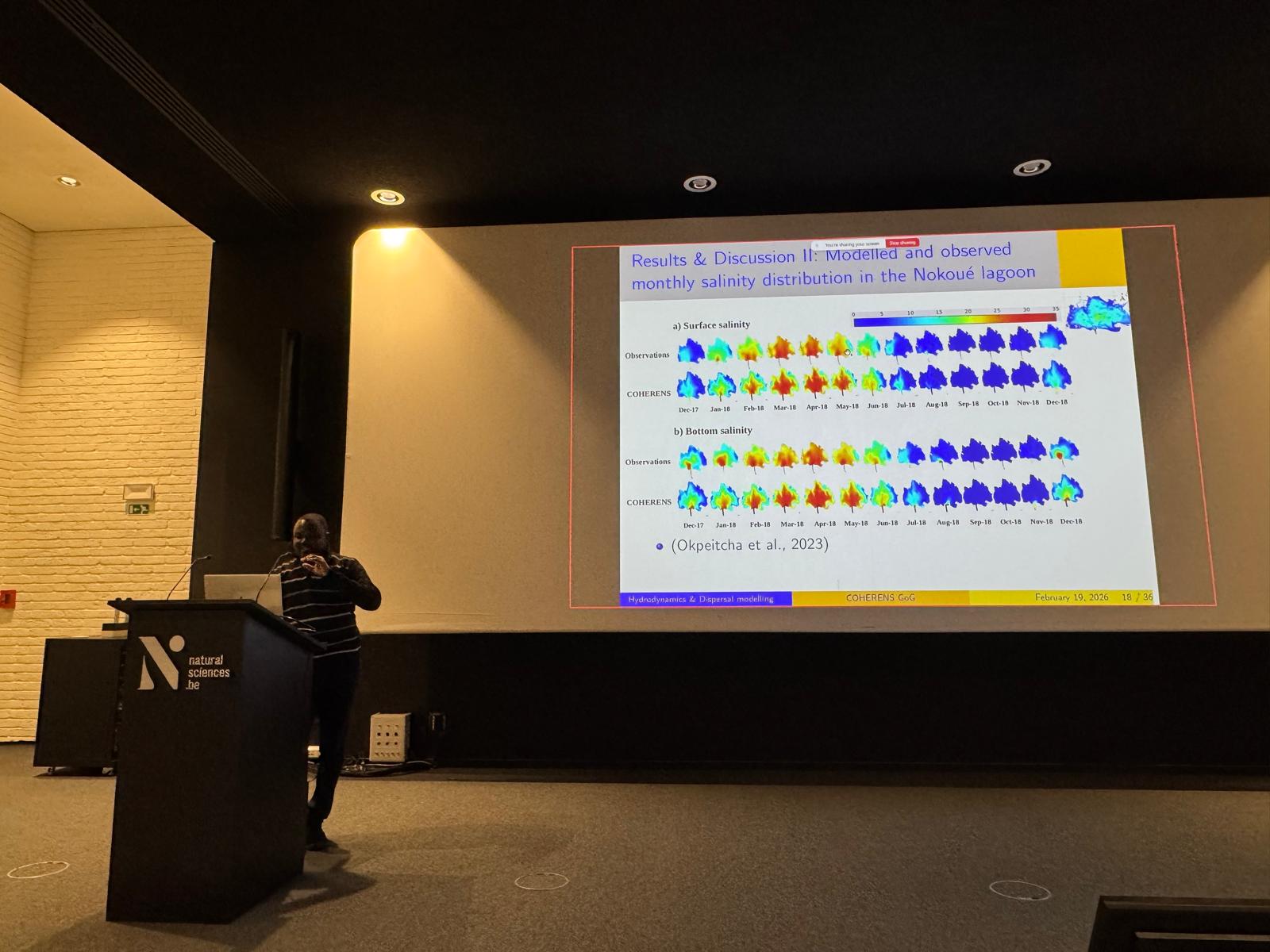

On February 19, 2026, Sylvain Gozingan brilliantly defended his doctoral thesis entitled “Developing a multi-scale modelling framework for coastal hydrodynamics and larval connectivity in the Gulf of Guinea, West Africa.” His work demonstrates that connectivity between the ocean and the Nokoué lagoon in Benin is primarily controlled by well-defined hydrodynamic mechanisms, playing a crucial role in the transport and entry of shrimp larvae into the lagoon—a key finding for the sustainable management of fisheries resources in Benin.

Sylvain Gozingan of the University of Abomey-Calavi in Benin publicly defended his doctoral thesis in physical oceanography and numerical modeling, entitled: “Developing a multi-scale modelling framework for coastal hydrodynamics and larval connectivity in the Gulf of Guinea, West Africa”. Following the defense, which took place on February 19, 2026, at the Institute of Natural Sciences, in the presence of all members of the jury, Sylvain was awarded the highest distinction for his doctoral thesis.

Research towards sustainable management

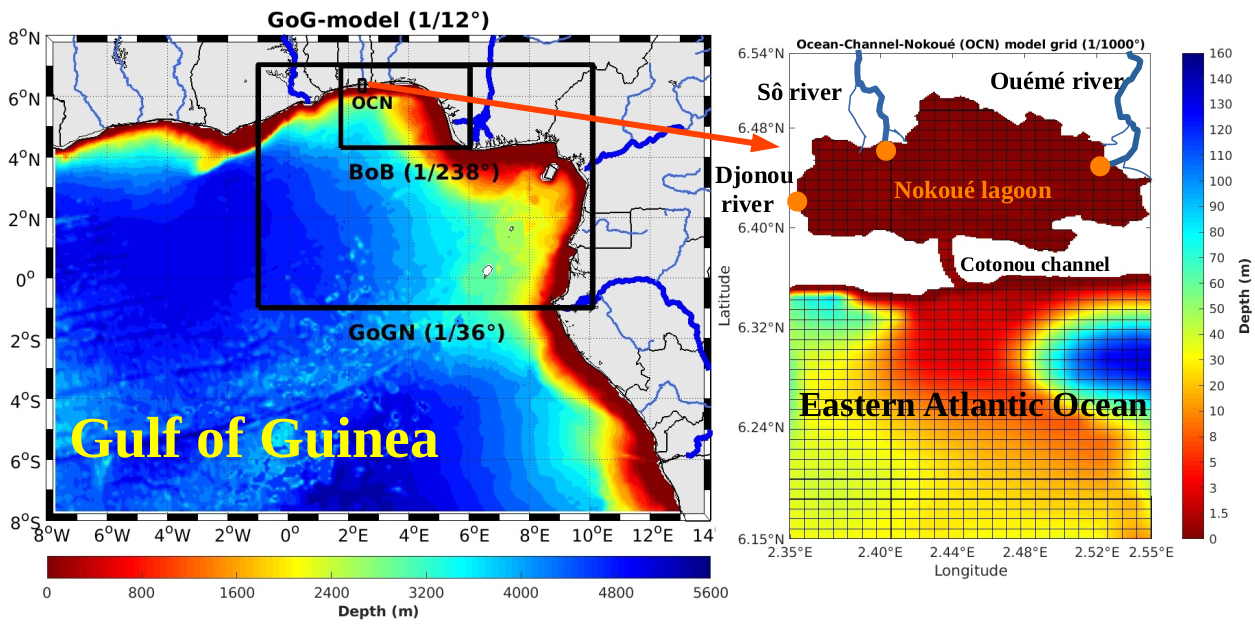

Sylvain Gozingan explains: “The research carried out as part of my doctoral thesis focuses on the development and application of coupled three-dimensional models, combining hydrodynamics and particle tracking, to study marine circulation and larval connectivity in the Gulf of Guinea, with a particular focus on the Nokoué ocean-channel-lagoon system in Benin. This has made it possible to identify the hydrodynamic mechanisms controlling connectivity between the ocean and the Nokoué lagoon for commercially important shrimp larvae.”

First, the results show that the entry of larvae into the lagoon is not random but depends on well-defined physical conditions. It is mainly favoured by specific tidal conditions, the existence of tidal windows and hydrodynamic windows of opportunity, with a particularly favourable period during the dry season (January-June).

Secondly, the study demonstrates that larval transport can be largely explained by passive drift mechanisms. This transport is dominated by the combined action of tidal currents, residual circulation, and wind-induced currents, without the need to invoke complex active larval behaviour at the scale studied.

Finally, the analysis of particle trajectories reveals that the larvae that actually reach the lagoon come mainly from the shallow coastal zone, in particular from regions where the depth is less than or equal to 15 m.

“Overall, these results strengthen the understanding of connectivity in the Nokoué ocean-lagoon system and provide valuable scientific information for predicting larval dispersal, a crucial element for the sustainable management of fisheries resources,” concludes Sylvain.

The results of the thesis were presented to local communities during a feedback workshops organized in Benin in 2024.

Interdisciplinary collaboration with Belgian and Beninese support

Sylvain already held a master’s degree in physical oceanography and applications, obtained in 2018 from the University of Abomey-Calavi. His thesis focused on applying an automatic algorithm for identifying and tracking vortices to a series of numerical potential vorticity fields, considered as a dynamic Lagrangian tracer. Since then, he has developed a passion for studying particles in marine ecosystems, using data analysis and numerical modeling.

Since February 2020, Sylvain has collaborated with the Institut de Recherches Halieutiques et Océanologiques du Bénin (IRHOB) and the ECOMOD team at the Institute of Natural Sciences. This collaboration took place within the framework of the Shrimp-I project (Application of the COHERENS model to improve shrimp stock management in Benin) and the Shrimp-II project (Application of the COHERENS model to the life cycle analysis of shrimp and oysters to better manage their stocks in Beninese waters). These projects were funded by the Directorate General for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid (DGD) under the CEBioS programme (Capacities for Biodiversity and Sustainable Development).

EMBRC-Belgium is a collaboration between various research groups from Ghent University, the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ), Hasselt University, KU Leuven, and the Institute of Natural Sciences, and is funded by Flemish and federal research funds. Within this EMBRC collaboration, the Institute of Natural Sciences strengthens the consortium with its monitoring activities and specialized research on artificial reefs.

EMBRC-Belgium is a collaboration between various research groups from Ghent University, the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ), Hasselt University, KU Leuven, and the Institute of Natural Sciences, and is funded by Flemish and federal research funds. Within this EMBRC collaboration, the Institute of Natural Sciences strengthens the consortium with its monitoring activities and specialized research on artificial reefs.

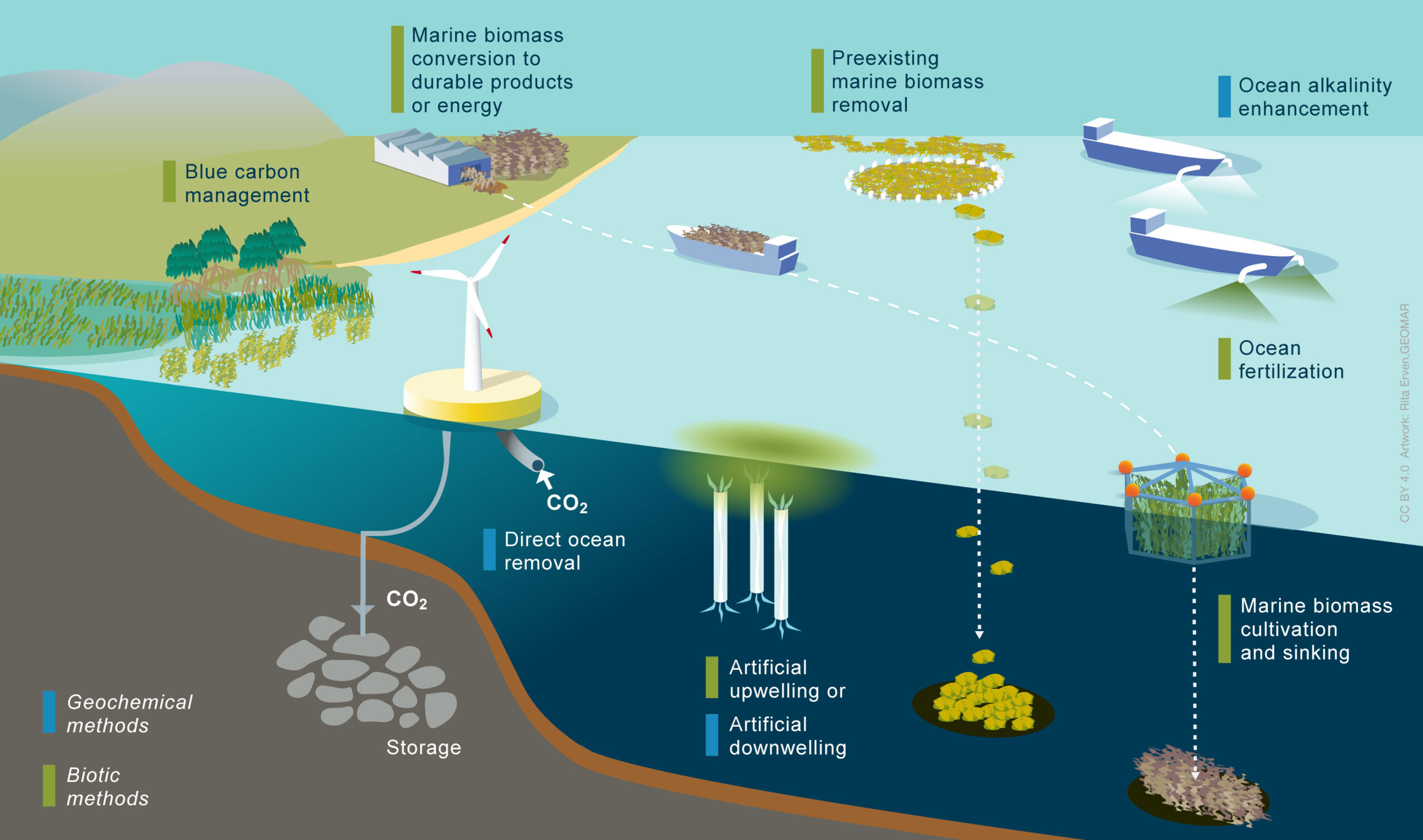

Monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) is a structured process to collect, disclose and independently verify data on mCDR activities. The process includes quantifying CO2 removals, durability, uncertainties and environmental impacts. Going forwards, science-based guidance to develop these robust, transparent and scientific MRV frameworks for mCDR is needed.

Monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) is a structured process to collect, disclose and independently verify data on mCDR activities. The process includes quantifying CO2 removals, durability, uncertainties and environmental impacts. Going forwards, science-based guidance to develop these robust, transparent and scientific MRV frameworks for mCDR is needed.