Co-location of marine activities, lithium extraction from the deep sea, overfishing of deeper-water species, and the unexpected ocean impacts of wildfires and of new biodegradable materials are among fifteen issues experts warn we ought to be addressing now.

An international team of experts has produced a list of 15 issues that are not currently receiving widespread attention but are likely to have a significant impact on marine and coastal biodiversity over the next decade (see below for full list).

The horizon scan involved 30 experts in marine and coastal systems from 11 countries in the global north and south, from a variety of backgrounds including scientists and policy-makers. The study was led by Dr James Herbert-Read and Dr Ann Thornton in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, and included Prof Dr Steven Degraer of the Marine Ecology and Management (MARECO) team of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS). The resulting paper ‘A global horizon scan of issues impacting marine and coastal biodiversity conservation’ was published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution on 7 July 2022.

This horizon scanning process has previously been used to identify issues that have later come to prominence. For example, a scan in 2009 gave an early warning that microplastics could become a major problem in marine environments, which is indeed the case now.

Seemingly Unexpected Issues

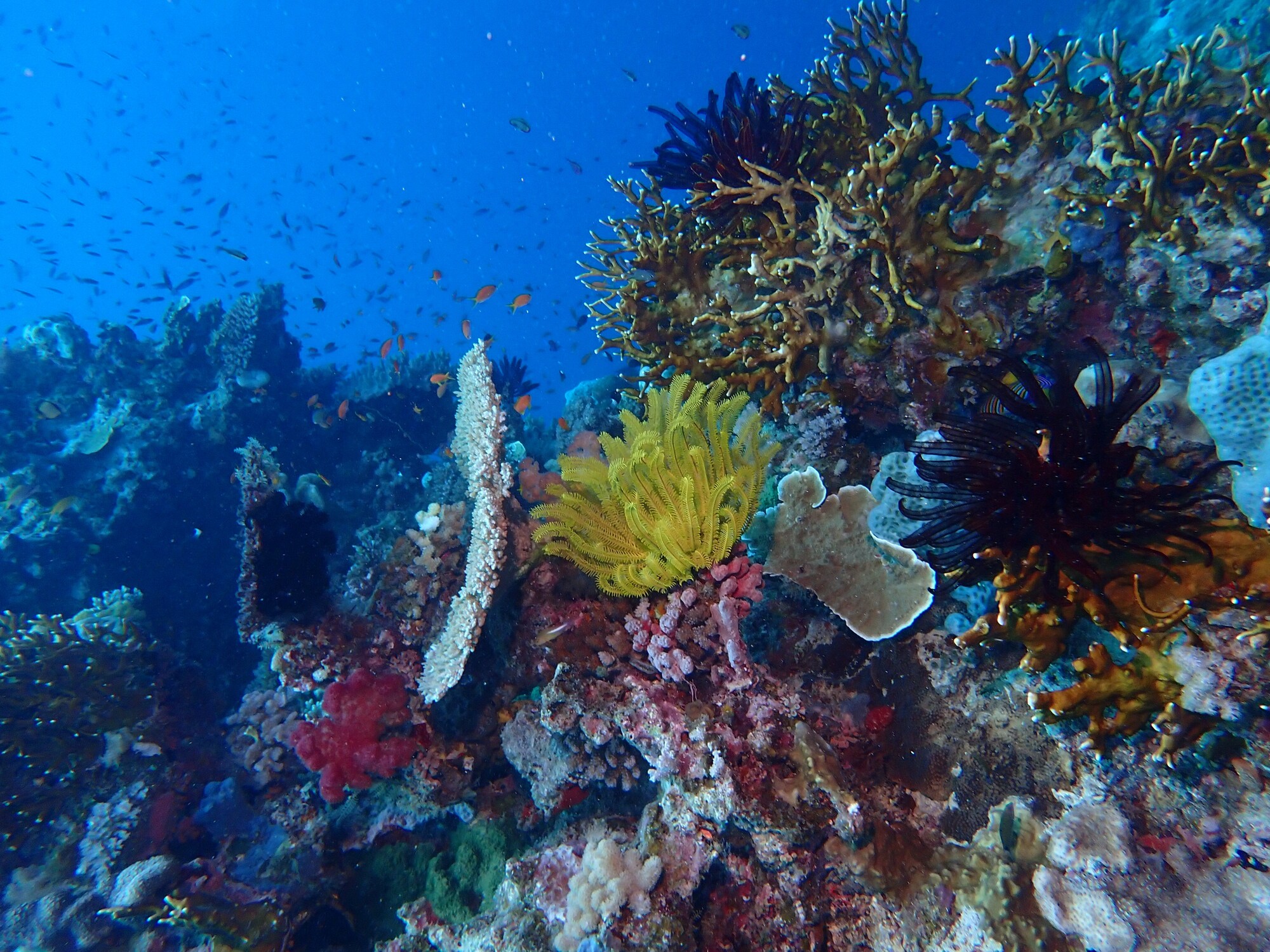

While there are many well-known issues impacting ocean biodiversity, including climate change, ocean acidification and pollution, this study focuses on lesser-known emerging issues that could soon have significant impacts on marine and coastal ecosystems. These issues include the effects of new biodegradable materials on the marine environment, the impacts of wildfires on coastal ecosystems, and an ‘empty’ zone at the equator as species move away from this warming region of the ocean.

“Marine and coastal ecosystems face a wide range of emerging issues that are poorly recognised or understood, each having the potential to impact biodiversity,” said Dr James Herbert-Read. He added: “By highlighting future issues, we’re pointing to where changes must be made today – both in monitoring and policy – to protect our marine and coastal environments”.

For example, the report highlights the potential impact of new biodegradable materials on the ocean. Although such materials are promoted as a solution to the waste problem, some of these materials are more toxic to marine species than traditional plastics. Herbert-Read said: “Governments are making a push for the use of biodegradable materials, but in many cases we don’t know what impacts these materials may have on ocean life”.

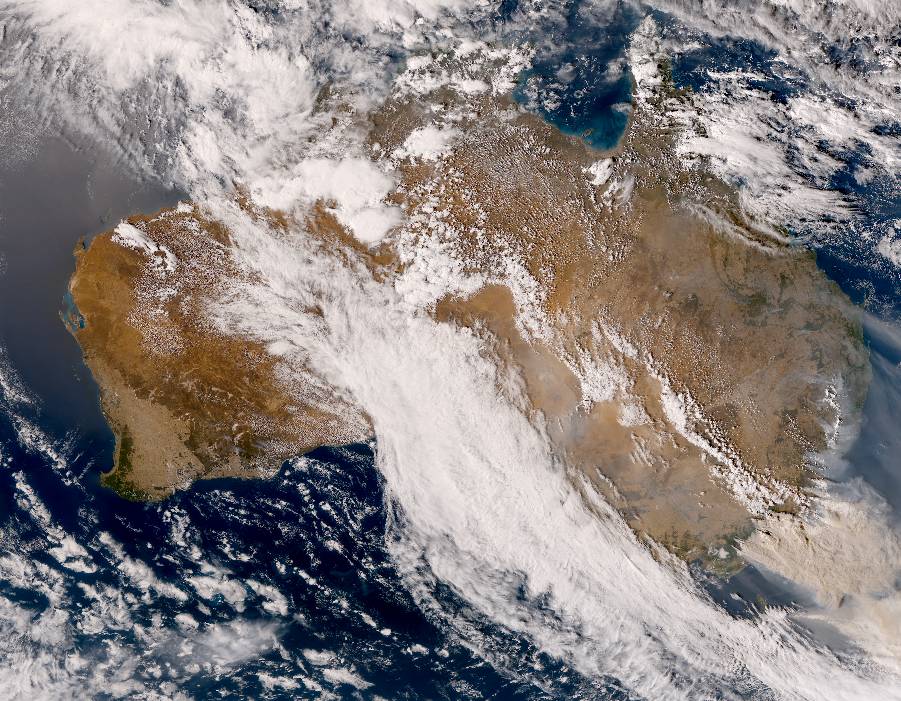

At first glance, the potential impact of wildfires on coastal and marine environments may also seem unexpected, but in addition to habitat destruction, wildfires can cause water pollution from ash and other debris, sediment and nutrient slugs that move many kilometres downstream and impact aquatic life along the way, and the emergence of harmful algal blooms.

Apart from fish moving away from the equator, the authors also warn that the nutritional content of fish is declining as a consequence of climate change. Essential fatty acids tend to be produced by cold-water fish species, so as climate change raises ocean temperatures, the production of these nutritious molecules is reduced. Such changes may have impacts on both marine life and human health.

Exploitation Issues

Several of the issues identified are linked to exploitation of ocean resources. For example, deep sea ‘brine pools’ are unique marine environments home to a diversity of life and have high concentrations of salts containing lithium. The authors warn that rising demand for lithium for electric vehicle batteries may put these environments at risk. They call for rules to ensure biodiversity is assessed before deep sea brine pools are exploited.

While overfishing is an immediate problem, the horizon scan looked beyond this to what might happen next. The authors think there may soon be a move to fishing in the deeper waters of the mesopelagic zone (a depth of 200m – 1000m), where fish are not fit for human consumption but can be sold as food to fish farms. “There are areas where we believe immediate changes could prevent huge problems arising over the next decade, such as overfishing in the ocean’s mesopelagic zone,” said Dr Ann Thornton. She added: “Curbing this would not only stop overexploitation of these fish stocks but reduce the disruption of carbon cycling in the ocean because these species are an ocean pump that removes carbon from our atmosphere”.

Far Away Issues?

Although some of the problems listed may seem far away, the study is also relevant in the Belgian part of the North Sea. Steven Degraer of RBINS clarifies: “Issues like how to properly manage the co-location of human activities at sea or the possible alteration of the nutritional content of fish due to climate change are of direct relevance also to well-studied areas like the southern North Sea”.

Because our waters are positioned on a busy shipping route, near a number of large ports, and count many different users (shipping, fisheries, renewable energy, sand extraction, dredging, tourism, …), it remains a continuous challenge to reconcile all activities on a limited surface so that the cumulative effects remain acceptable and mitigable. And, of course, the effects of climate change are not exclusive to tropical regions.

Driving Policy Change and Practices

Not all of the predicted impacts are negative. The authors think the development of new technologies, such as soft robotics and better underwater tracking systems, will enable scientists to learn more about marine species and their distribution. This, in turn, will guide the development of more effective marine protected areas. But they also warn that the impacts of these technologies on biodiversity must be assessed before they are deployed at scale.

“Our early identification of these issues, and their potential impacts on marine and coastal biodiversity, will support scientists, conservationists, resource managers, policy-makers and the wider community in addressing the challenges facing marine ecosystems,” said Herbert-Read.

The main aim of the study is therefore to raise awareness and encourage investment into full assessment of the predicted issues now, and potentially drive policy change, before the issues have a major impact on biodiversity.

By providing an early warning for the listed issues, the authors work in synergy with other ongoing processes. The United Nations has designated 2021-2030 as the ‘UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.’ In addition, the fifteenth Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity will conclude negotiations on a global biodiversity framework in late 2022. The aim is to slow and reverse the loss of biodiversity and establish goals for positive outcomes by 2050.

This research was funded by Oceankind.

The full list of issues identified by the report

Ecosystem impacts

- Wildfire impacts on coastal and marine ecosystems

- Coastal darkening

- Increased toxicity of metal pollution due to ocean acidification

- Equatorial marine communities becoming depauperate (lacking variety) due to climate migration

- Altered nutritional content of fish due to climate change

Resource exploitation

- Untapped potential of marine collagens and their impacts on marine ecosystems

- Impacts of expanding trade for fish swim bladders on target and non-target species

- Impacts of fishing for mesopelagic (middle-depth) species on the biological ocean pump

- Extraction of lithium from deep-sea brine pools

Novel technologies

- Co-location of marine activities

- Floating marine cities

- Trace element contamination compounded by the global transition to green technologies

- New underwater tracking systems to study non-surfacing marine animals

- Soft robotics for marine research

- Effects of new biodegradable materials in the marine environment