Aquaculture at sea and the decommissioning of offshore wind farms come with many opportunities and challenges. For the efficient development of future policy on these activities, it is essential that the priorities and concerns of the many stakeholders are heard and integrated in an open and transparent manner into a broad-based vision that policymakers can subsequently work with.

To address this, the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences launched two separate participatory trajectories on these themes on behalf of the Marine Environment Department of the Federal Public Service Public Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment and Minister for the North Sea, Vincent Van Quickenborne. More than 50 different organisations responded to this interactive cooperation initiative.

Steven Degraer (Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences): “Getting stakeholders to talk to each other always yields surprising insights and this for all parties around the table. It is the way to get to know each other, share insights and look for a sustainable future for the sea together.”

The kick-off of both trajectories took place in Bruges on Tuesday 18 October 2022. Stakeholders met almost monthly, and also worked intersessionally on vision-building. During a closing event on Monday 15 May, also in Bruges, the resulting visions around aquaculture and decommissioning of offshore wind farms in the Belgian part of the North Sea were presented to the trajectories’ participants and the press.

Aquaculture

Key elements identified within the stakeholder consultation on marine aquaculture are:

Sustainable food production for our and future generations is the primary goal of aquaculture in the Belgian part of the North Sea. Various organisms are suitable for this purpose. First and foremost, oysters and mussels are considered, but also algae, whelks, scallops and other bivalves, crustaceans and fish. Aquaculture of jellyfish, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, sea grasses and even bacteria is also theoretically possible. To what extent combining the farming of different species (integrated multitrophic aquaculture) is possible our Belgian North Sea needs further investigation.

Other economic activities (such as fuel and cosmetics production, tourism) can be linked to aquaculture and thus play a role in eliminating residual flows.

Optimal use of available space is one of the main concerns. Potential spatial conflicts with other users of the sea were raised, as well as opportunities for multiple use of space.

Attention to the environment also scores very high. Here, there is not only concern about possible forms of negative impact, participants also see opportunities to combine aquaculture with nature conservation, nature restoration and coastal protection.

Basic and preconditions

Several conditions must be respected when looking for suitable sites and forms of aquaculture.

Important basic conditions are:

- To start with, it is important to understand in which locations the target species thrive. This varies between potential target species and depends on species-specific abiotic and biotic factors.

- Sustainable aquaculture should be extractive, meaning that no additional nutrients or drugs should be added. It should also not exceed the carrying capacity of the surrounding natural ecosystem.

- In nature reserves, aquaculture will no longer be allowed before the areas are in good conservation status, and then only with native species.

- Aquaculture products must comply with common food safety requirements.

Additional preconditions that should be pursued to the maximum extent possible relate to personal and marine traffic safety, multiple space use, social acceptability, environmental damage, cooperation, ecological footprint, engineering/technical aspects, socio-economics, legal and insurance aspects and broad governance context.

The future

A North Sea in good conservation status is a prerequisite to provide sufficient carrying capacity for aquaculture. To promote opportunities and mitigate concerns, well-designed licensing criteria must be established. Administrative obstacles and red tape must be removed. The development of a central monitoring and warning system and a pooled knowledge platform would offer many benefits. Targeted grants could help address knowledge gaps and develop opportunities.

In the next phase, additional data and map material will be collected to create an opportunity map for aquaculture in the Belgian part of the North Sea, linked to the predefined basic and boundary conditions. Taken together, these elements will form a solid basis for policy support.

Cooperation and coordination between the North Sea countries is also desirable, including in terms of drafting uniform European regulations.

Vincent Van Quickenborne, Minister for the North Sea: “The North Sea is a breeding ground for innovation. With no fewer than 53 partners, we have joined forces in recent months on two important themes. For instance, despite our small North Sea, we have a lot of space to do aquaculture. E.g. between the windmills. We are now mapping those areas. We are looking into species of which we can combine the cultivation. And we are looking for European money to invest in this.”

Decommissioning of offshore wind farms

The licences to operate Belgium’s already operational wind farms date back 10 to 15 years. The decommissioning of that first generation of wind turbines is now approaching. Just as the installation of these farms was pioneering work, their decommissioning will be too. Moreover, in the time that has passed, many questions arose about the phased decommissioning process in the period 2034-2047. On the one hand, new technologies are succeeding at lightning speed and, on the other, new insights are constantly emerging around the interaction between wind farms and biodiversity.

New technologies: New options for decommissioning offshore wind farms are being developed, with regard to techniques, materials and cost. For example, options for repurposing and recycling blades and ways to remove monopile foundations in their entirety from the ground are being explored.

Biodiversity: Monitoring the ecological effects of wind farms shows that additional biodiversity has been created in and around the offshore wind turbines, the so-called artificial reef effect. The new hard substrates underpin a rich underwater fauna of invertebrates, which in turn attracts various fish species, bird species and marine mammals.

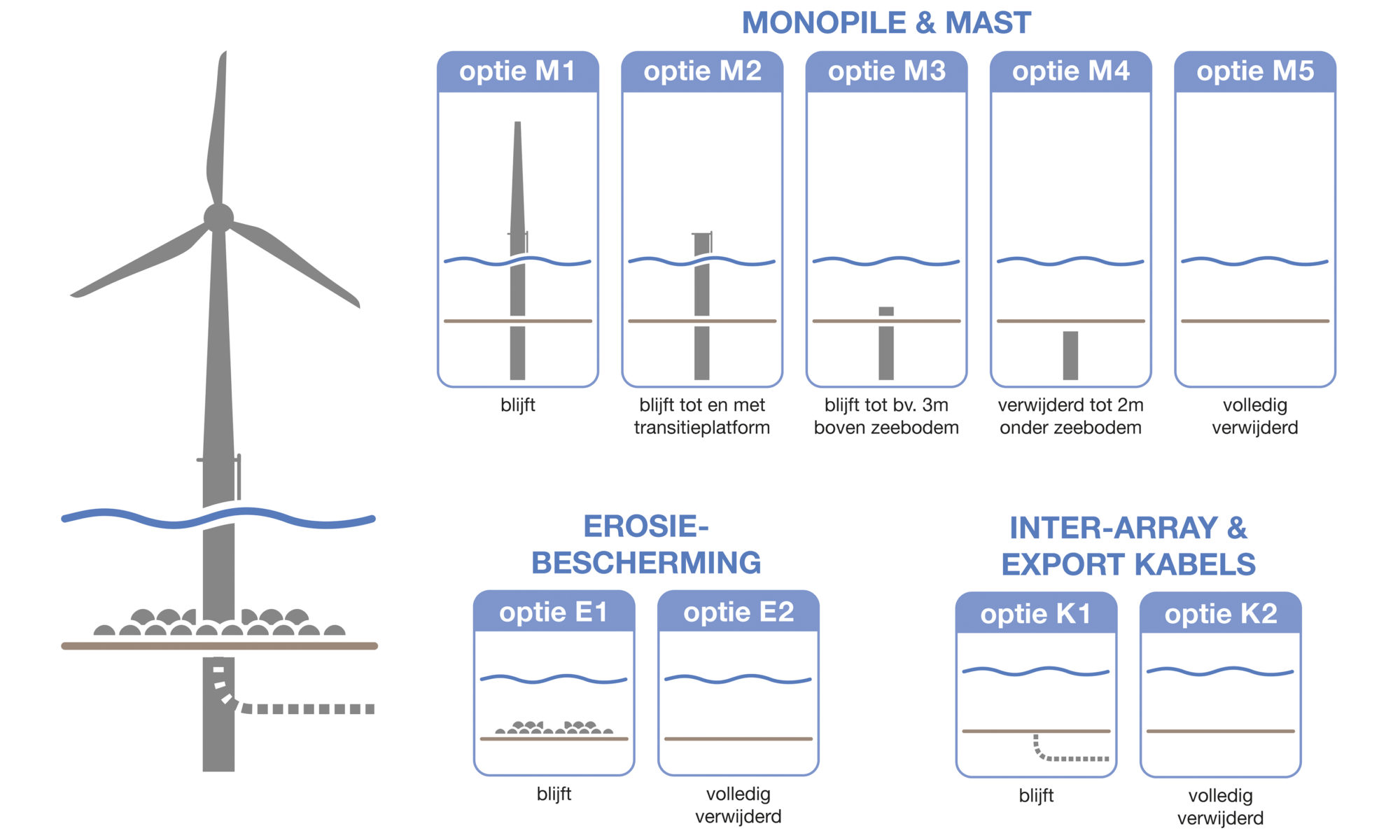

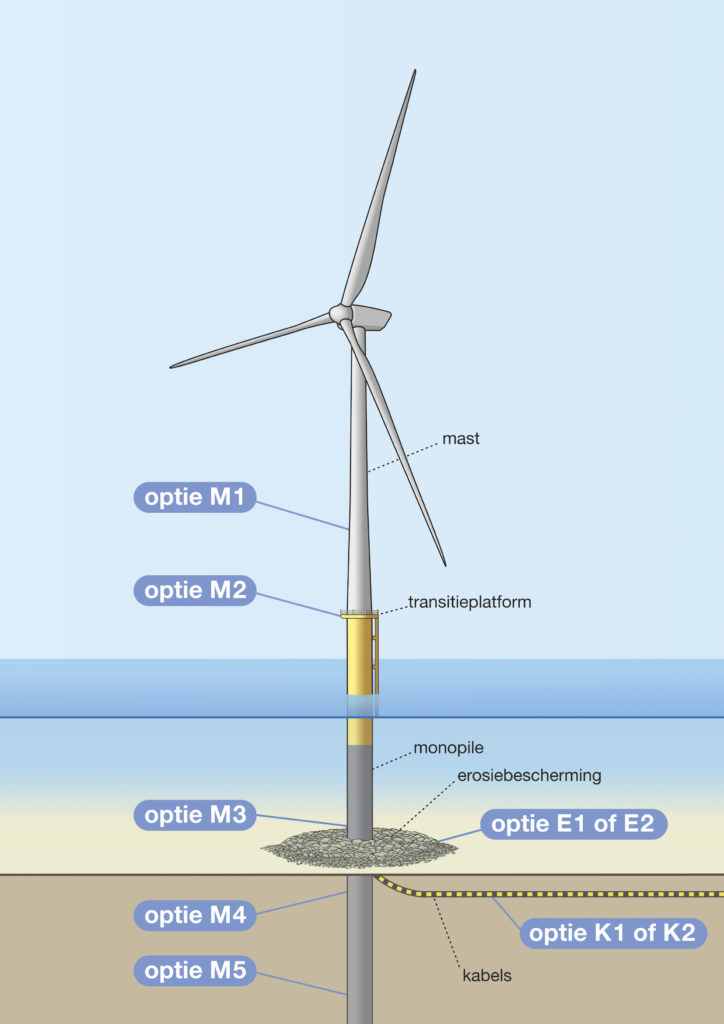

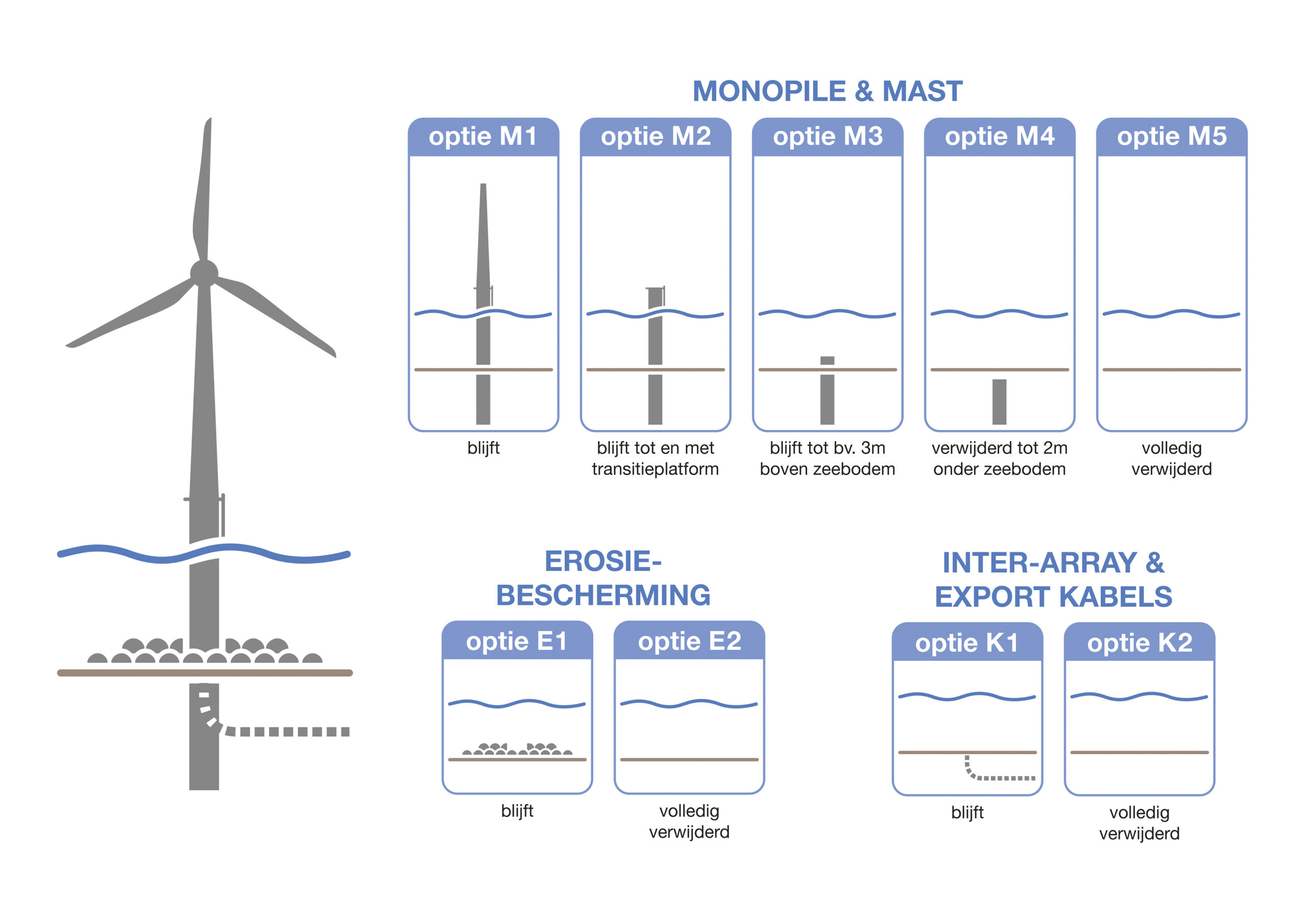

Decommissioning options

To decommission offshore wind farm infrastructure, there are several theoretical options. The foundations can either be completely or partially removed or remain entirely on site. Erosion protection layers and cabling can also be removed or remain on site. The majority of the participants to the process of vision creation favoured complete removal of all man-made structures.

The naturally occurring and desirable fauna of dynamic sandy substrates is adapted to high dynamics, allowing it to withstand a temporary disturbance caused by decommissioning activities well and recover quickly. The new biodiversity created as a result of the artificial reef effect is not considered of such interest in a naturally dynamic sandy-bank ecosystem to be left untouched because it is a habitat that does not naturally occur at that site. Moreover, when decommissioning in the context of repowering, hard substrate will again be provided in the form of a new wind farm, so that those additional habitat, shelter and resting opportunities will recover in the short term and in phases.

Leaving some of the infrastructure in place could be useful for attaching structures for aquaculture, passive fishing or as a research base (sensors, testing new technologies, etc.), for example, but these functionalities could equally be envisaged for yet-to-be-built wind turbines. In addition, retaining (part of) the monopiles and leaving erosion barriers and cables in place do not outweigh the disadvantages of insecurity and the missed opportunity to reuse materials.

In contrast, wind farm operators, who after all have to carry out and pay for decommissioning, are rightly concerned about whether it will be both feasible and affordable engineering-wise to completely remove a monopile. Also, removing the erosion protection, even if it is to be reused for the same purpose when repowering, is a costly and time-consuming activity. Thus, further research and consultations still appear necessary to identify the feasibility and the advantages and disadvantages of the alternative decommissioning scenarios (complete removal, partial removal or complete abandonment of wind farm infrastructure, including erosion protection layers). By starting this in time, with the vision process as the first component, we give time to the public and private partners involved to prepare.

Useful info for future wind farms

The findings from the participatory process also offer insights into how future wind farms can be optimally designed, taking into account the decommissioning phase. In particular, promoting circular use of materials offers sustainability opportunities.

The Princess Elisabeth zone contains zones of natural hard substrate, a low-dynamic habitat with high ecological value. Decommissioning activities will therefore have a greater impact here than on the dynamic sandy soils where the current wind farms are located. On the other hand, in the gravel beds of the Princess Elisabeth zone, many win-wins can be achieved by implanting artificial hard substrate such as wind turbines and erosion protection layers. Whereas in the first zone it is advised, for reasons of natural value, to remove everything when decommissioning, in the Princess Elisabeth zone it remains to be seen how to avoid disturbance of the gravel beds during decommissioning as much as possible, and how to preserve the natural value of the artificial hard substrate in the vicinity of the gravel beds as much as possible.

Vincent Van Quickenborne, Minister for the North Sea: “Our country is among the world leaders in offshore wind. Now we are going to have to decommission the first generation of offshore wind turbines within a few years. We are now figuring that out with all kinds of agencies and researchers. Because we also want to decommission in a sustainable way. By being a pioneer in this activity, we ensure that our companies will once again be world-class specialists.”

The final reports of the stakeholder projects ‘Aquaculture’ and ‘Decommissioning of offshore wind farms’ will be available for consultation from mid-June on the Marine Environment Service website, specifically in the ‘North Sea Publications’ section (Dutch – French).