While Belgium emerged as a world leader in the offshore wind industry, the Belgian scientists that monitor the environmental impact of offshore wind farms have also developed extensive knowledge and expertise. Shortly after the first Belgian offshore wind zone was completed (the world’s biggest to be operational), the monitoring consortium presents its latest conclusions and recommendations in a new report. Different components of the marine ecosystem are impacted in different ways. Therefore, the environmental impact is not a black or white story. Balancing the energy and biodiversity crises was never expected to be an easy task. The monitoring continues, as does the development of mitigation measures where needed.

While Belgium emerged as a world leader in the offshore wind industry, the Belgian scientists that monitor the environmental impact of offshore wind farms have also developed extensive knowledge and expertise. Shortly after the first Belgian offshore wind zone was completed (the world’s biggest to be operational), the monitoring consortium presents its latest conclusions and recommendations in a new report. Different components of the marine ecosystem are impacted in different ways. Therefore, the environmental impact is not a black or white story. Balancing the energy and biodiversity crises was never expected to be an easy task. The monitoring continues, as does the development of mitigation measures where needed.

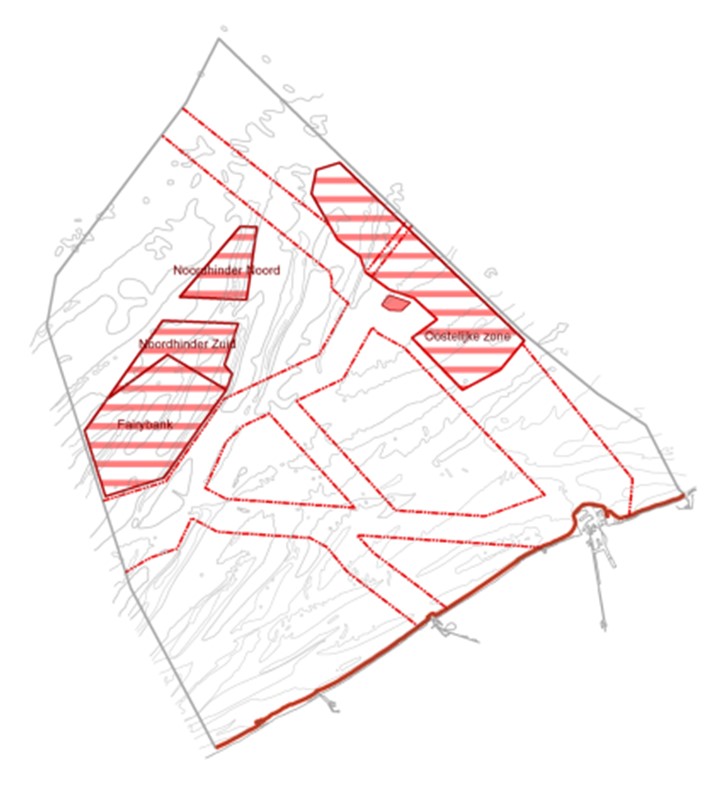

The European Commission imposes targets for the contribution of renewable energy sources to the total electricity production by all Member States (Directive 2009/28/EC). For Belgium, 13 % of the total energy consumption must be covered by renewable energy by 2020. Offshore wind farms in the Belgian part of the North Sea make an important contribution, and a first zone of 238 km² along the border with the Netherlands was reserved for wind farms to achieve this goal. At the end of 2020, after 12 years of construction, the wind farms in this zone were completed. A total of 399 turbines is now operational in eight wind farms, with an installed capacity of 2,26 Gigawatts (GW) and the production of an average of 8 TWh. This represents approximately 10 % of Belgium’s total electricity demand, or 50 % of the electricity needs of all Belgian households. At the moment, the construction works have ended, but a second area for renewable energy of 285 km² is foreseen in the new Marine Spatial Plan for the period 2020-2026, intending to add a minimum of 2 GW to the total Belgian offshore wind energy production capacity.

Balancing the energy and biodiversity crises

It is very challenging to find a balance between the installation of offshore wind farms as measures to combat the energy/climate crisis and acceptable environmental impacts in the light of combatting the biodiversity crisis. Both crises need to be tackled, but within conditions that do not worsen the other crisis. It also needs to be kept in mind that the Belgian offshore wind farms are not unique cases: on the scale of the southern North Sea, offshore wind farm areas are also foreseen in the adjacent Dutch Borssele zone (344 km²) and in the French Dunkerque zone (122 km²). Cumulative ecological impacts will hence continue to be a major concern in the years to come. Only by closely cooperating towards the common goal of increasing the production of renewable energy with acceptable ecological impacts, science, industry and policy can jointly address the challenge.

Permits and Monitoring

Before a wind farm can be installed in Belgian marine waters, developers must obtain a domain concession and an environmental permit. This permit imposes a scientific monitoring programme to assess the effects of the project on the marine ecosystem and includes terms and conditions that are intended to minimise and/or mitigate aspects of the impact that are evaluated to be unacceptable. The monitoring programme is carried out by the WinMon.BE consortium. Annual reports that target marine scientists, managers, policy makers and offshore wind farm developers are published in the ‘Memoirs of the Marine Environment’-series of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

The monitoring programme covers a broad range of ecosystem components from soft sediment and (artificial) hard substrate invertebrates and fish to seabirds and marine mammals, as well as their interactions. In other words, the monitoring does not only focus on the quantification of the extent of the impacts on the marine ecosystem but also aims at revealing the cause-effect relationships of certain impacts.

Long-term Insights

The newest report ‘Environmental Impacts of Offshore Wind Farms in the Belgian Part of the North Sea. Empirical Evidence Inspiring Priority Monitoring, Research and Management’, presents an overview of the scientific findings of the Belgian offshore wind farm environmental monitoring programme (WinMon.BE), based on data collected up to and including 2019.

Because the different studied ecosystem components are impacted by offshore renewable energy developments in different ways, and at different spatial and temporal scales, the environmental impact cannot be easily summarised as positive or negative. The main conclusions and recommendations of the latest studies include:

- The use of double bubble curtains proved partially effective to reduce underwater sound associated with the installation of 8 m diameter monopiles to levels in line with national standards.

- Following a review of compliance with relevant environmental license conditions, an optimization of the use of acoustic deterrent devices and noise mitigation measures, and formalizing marine mammal surveys, are recommended.

- Over 80% of the estimated number of seabirds colliding with turbines in Belgian waters are large gulls. Wind farm location, layout and turbine size determine the expected number of collisions.

- Future research should address specific aspects of the impact on individual birds and populations, and mitigation: correlation between displacement and wind farm characteristics, large gull movements and an empirically informed species-distribution model to support marine spatial planning.

- Sediments become finer and organically enriched close to jacket foundations, accompanied by higher abundance and diversity of macrofauna. Typical coastal species from productive waters are colonizing the now finer sediments around the turbines.

- Nine years after construction, the first signs become apparent that wind farms can act as refugia for fish that prefer soft sediments (e.g. plaice), probably resulting from fisheries exclusion and increased food availability, while the reef effect expands to soft sediments between the turbines (colonized by invertebrates of hard substrates).

- Offshore wind farms influence the local food webs from the basis, with colonizing fauna reducing primary producers, to higher trophic levels, with several fish species intensively feeding on the colonizing fauna.

Future Monitoring

The fact that the first Belgian zone for offshore wind farms has been fully completed does not mean that the monitoring now comes at an end. Although the understanding of the effects of wind turbines on the marine environment and its inhabitants has grown significantly over the past 10 years, there is still much to learn about the longer-term environmental impact of offshore wind farms. To allow for that, the current cooperation model in which scientists and the offshore wind industry document the impact of the operational phase of the wind farms will continue to remain active. “Examples of fields that we have started to explore but cannot yet report on include the improvement of modelling of bird and bat collision risks, the monitoring of the impact of continuous underwater sound that is generated by operational turbines, and the longer-term effects on fish populations. It also remains unknown how fouling communities on the wind turbines will further evolve, and how the observed behavioral changes impact the individual fitness, reproductive success and survival of marine animals.” says Steven Degraer, coordinator of the WinMon consortium and head of the Marine Ecology and Management team of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Degraer continues “Extending the cooperation will also allow to further evolve in the field of designing, testing and improving mitigation measures to directly manage unwanted effects on the marine ecosystem.”

Monitoring activities will also have to be initiated in the same way in the second Belgian offshore wind zone once the construction will start there. The collection of baseline data on the state of the marine ecosystem in that area, on which a future assessment of changes will rely, is already ongoing. In addition, rapidly evolving technology and construction practices require frequent reassessment of observed impacts.

In the meantime, the Belgian expertise on the monitoring of the environmental impact of offshore wind farms is also getting international attention. “Monitoring plans that are inspired by the Belgian work are being set up in both France and the United States, so Belgium should not only be considered a world leader in the offshore wind industry, but also in the monitoring of their environmental impact.” Degraer concludes.

The Monitoring Programme WinMon.BE is a cooperation between the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), the Research Institute Nature and Forest (INBO), the Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (ILVO) and the Marine Biology Research Group of Ghent University, and is coordinated by the Marine Ecology and Management team (MARECO) of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.