Sorry, this entry is only available in Français and Nederlands.

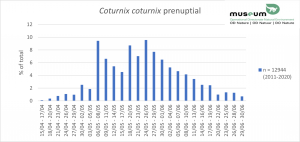

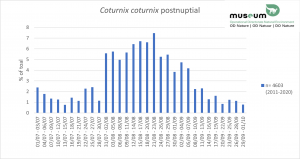

Coturnix coturnix

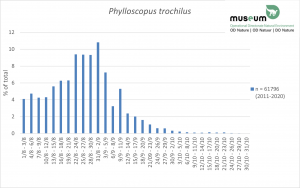

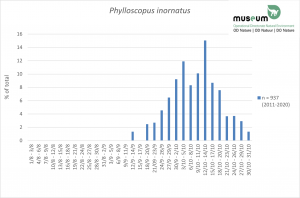

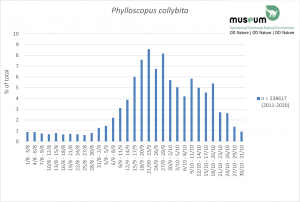

Phylloscopus sp

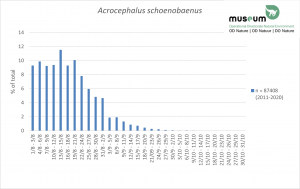

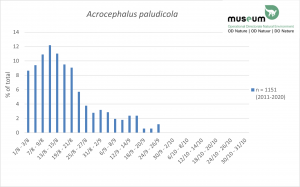

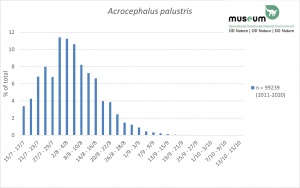

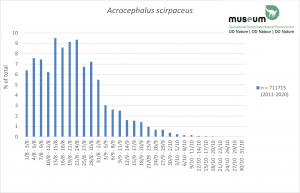

Acrocephalus sp

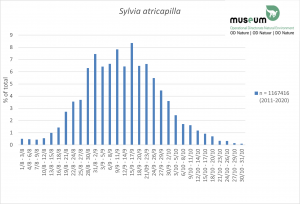

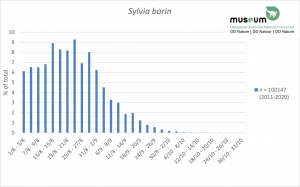

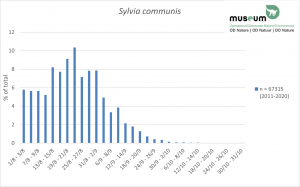

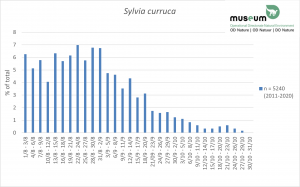

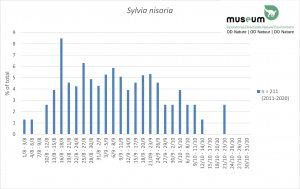

Sylvia sp

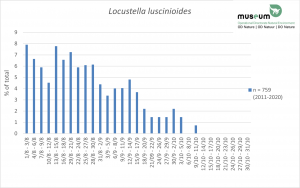

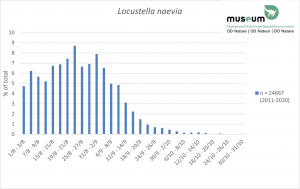

Locustella sp

Post-breeding migration phenology for birds ringed in Belgium 2011-2020

Migration is a crucial phase in the annual cycle of wild birds.

In some cases migration is innate, in others it is learned. But it is always a question of successfully joining one area to another, sometimes, often, thousands of kilometres away.

The journey requires remarkable abilities in terms of orientation, reaction to weather conditions, choice and availability of stopover places. The ability to feed efficiently during stopovers in order to replenish the energy reserves used during the first leg so as to be able to cover the next, and so on, is also crucial.

The phenology – the timing – of migration is an essential parameter in successful migration. The bird must leave in time to reach its destination site at the right moment, taking into account the stages to be covered and the food resources available from the beginning to the end of the journey. In the case of insectivorous passerines, these resources are essentially a function of the annual cycle, which in turn depends on the local weather.

Some species/populations consistently adapt their migration timing. Others seem to be “set” on a genetically predetermined schedule.

But what happens when the weather conditions are peculiar, when the climatic situation changes rapidly? To what extent do different bird species react appropriately? And if some do not, to what extent does this influence the evolution of their populations in terms of abundance and distribution?

By studying the migration phenology of different bird species ringed in Belgium during migration, we wish to contribute to this evaluation.

This first presentation of results compiles, in three-day periods, the ringing data collected throughout Belgium over the last 10 years. The results are expressed as a percentage of the total number of birds, from the species concerned, ringed during the reference period. The sample size (“n”) is presented next to each graph. These data are particularly robust considering the sample sizes in relation to the high density of their harvest – the land area of Belgium being ‘only’ 30,528 km².

The inter-annual variation in peak abundance will be presented in a second step.

Thanks to all the RBINS ringers who contributed to the collection of these data and to Paul Vandenbulcke who wrote papageno, the software for encoding these data.

Transmitter research on storks from the Zwin Nature Park

On Monday 29 June 2020, four new young white storks were equipped with transmitters in the Zwin Nature Park in Knokke-Heist. As such they follow in the footsteps of the three juvenile stork who were equipped with transmitters here in 2019, in collaboration with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Thanks to the transmitters, the scientists are able to continuously monitor the storks and obtain information about the migration routes, the wintering areas and the dangers the storks face. The research also makes it possible to estimate the consequences of changing conditions during the storks’ migration and wintering.

For information on the history of white storks in the Zwin Nature Park, in Belgium and in Europe, and for details on the design and technical aspects of the Belgian transmitter research, we refer to the article that was published in 2019. In this contribution the focus is on what the transmitter-storks from 2019 have taught us in the meantime, and on the continuation of the research.

Winter Adventures

The route followed by the three young Zwin-storks (Emily = red, Reinout = green, Hadewijch = blue) after being equipped with a transmitter on 26 June 2019 is summarised in the following animation, and commented upon in the text underneath.

After installing the transmitters, the young storks stayed in their nests for another two weeks. On 10 July the first flights were registered, the following weeks the area around the Zwin was extensively explored. The big departure took place on 21 August. The three birds departed together (no doubt in the company of other birds of the same species, but not their parents – it is known that they spend the winter in the Zwin Nature Park) and crossed France in no less than 6 days. On 30 August, meanwhile in northern Spain, they separated their ways.

- Emily turned out to be in the biggest hurry. On September 1st she was already near Gibraltar, and on September 23rd she crossed ‘the Strait’ to Morocco. After some wandering around in the north of that country she finally settled in a fixed winter area around mid-November. But things didn’t end well for her: on 20 February she flew into a high-voltage pylon and got electrocuted.

- Reinout, Emily’s sibling, on the other hand, was the least hurried of the trio. He stayed near Madrid until the beginning of October, before descending further to the south of Spain. And there he stayed, the winter was spent in the region of Seville. Mid-March he started his return journey, passing Belgium (where he spent one night) on 12-13 April, and then flying back and forth in the central Netherlands and the neighbouring part of Germany.

- Hadewijch (from another nest) stayed in N-Spain until mid-September, but finally made the crossing to Africa on September 30th. There she also wandered around, to settle in a fixed area in the north of Morocco at the end of November (though another area than Emily). At the end of March 2020 she left this area again, and started heading north. After a long stop in central France (mid-April – end of May) she then flew straight back to the Zwin Nature Park, where she arrived on 3 June and is still present today.

Interesting Findings

So far only three storks were followed during one year, so we are talking about a small sample and have to be cautious about linking strong conclusions to the results. But there are certainly some interesting observations:

- the three birds left together and stayed together for a considerable distance (as far as N-Spain)

- even after the split-up, they repeatedly visited the same areas, but at different times → points towards potentially exceptional importance of certain areas

- visits to landfill sites are a striking feature → interesting in relation to the important question of the impact of the European ban on open landfill sites (soon to be applied in the Iberian Peninsula) on species that have learned to look for food here

- American crayfish, an introduced exotic species, are a sought-after snack in the Spanish rice fields.

- one bird stayed in Europe, but the two that reached Africa didn’t cross the Sahara either

- when the birds settle for the winter, the range suddenly becomes very small

- electrocution is a real danger to large birds (confirmation)

- young birds show a great lust for wandering and start the return journey rather late, but a return to the region of birth is already possible in the first year

Further Research

Due to the small sample and the limited time span of the investigation so far, the above findings should not yet be considered to be significant conclusions. That is why the 2019 storks are still being monitored, and on 29 June 2020 four more storks were equipped with transmitters at the Zwin Nature Park (watch the video!). This time they originate from three different nests. The intention is to further increase the number of storks in the next few years. By the way, the transmitters remained unchanged compared to 2019. They weigh only 25 grams (less than one percent of the body weight) and are very sustainable. Working on solar energy, they transmit the accurate data collected by their GPS via the GSM network. When there is no range, everything is stored in an internal memory, and transmitted when possible. And there is also communication with the transmitters in both directions, e.g. the frequency of the transmission of location details can be adjusted.

Also the traditional ringing research remains important for building insights and formulating answers to the challenge of protecting storks, and migratory birds in general. After all, it is not enough to protect migratory birds in their breeding areas, this is also necessary in the winter quarters and along the entire migration route.

The results of the research can be followed on the website of the Zwin Nature Park – Operatie Ooievaar.

Names for the Storks

We are still looking for names for the four newly-equipped storks. Proposals can be submitted until 10 July, accompanied by a short justification for the proposed names. On 15 July the chosen names will be announced.

Interesting to know is that the sex of storks is almost impossible to determine externally. Only during mating can it be seen with certainty which position is taken by the two partners. Therefore, the sex of the young birds from 2019 is not yet known. It is quite possible that Reinout is the only female, and that the names Emily and Hadewijch were assigned to males. Maybe choose gender-neutral names? For the birds from 2020, however, the sex will soon be known, as some feathers have been collected for DNA analysis.

As an international airport for birds, the Zwin Nature Park is a knowledge and expertise centre for bird migration. In addition to ringing storks and installing transmitters, the Zwin Nature Park also focuses on ringing of other bird species. From 1 August to 7 November 2020, ringing will take place almost every day, and the public will also be able to observe this activity. In Belgium, the scientific ringing of birds is coordinated by the BeBIRDS group of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS).

RBINS and Zwin Nature Park install GPS transmitters on white storks

In the Zwin Nature Park in Knokke-Heist three young storks were provided with a transmitter at the end of June. Thanks to their transmitters, the movements of these storks can be followed at all times. With this study, the Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences and the Zwin Nature Park want to document the consequences of changing conditions in the wintering areas on the migration behaviour of the storks.

Since Leon Lippens started an introduction programme for white storks Ciconia ciconia in the Zwin Nature Park in 1957, about five hundred young have hatched here (the first in 1965). More than 300 of them were equipped with a scientific ring, within the framework of the long-term research tradition and cooperation with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. The majority were reported at least once (on average five times per reported stork), mainly along an axis towards the southwest, through the western half of France and central Spain. The furthest observation of a Zwin-ooievaar came from Algeria, at 2,164 kilometres from the Zwin. But Belgian storks have also been reported to spend the winter in West Africa, south to Senegal and Mali. The white stork is one of the species for which the Zwin has been designated as a special protection area under the EU Birds Directive.

This year the Zwin population counted 13 breeding pairs. In the wider area, however, 27 additional pairs were documented (region Knokke-Heist, Damme, Bruges, and across the Dutch border), so that the total regional population in 2019 was no less than 40 breeding pairs. A few years ago, the feeding of storks in the Zwin was stopped, which probably contributed to their distribution over a larger area.

Transmitters in addition to rings

In 2019, the Zwin also devoted attention to the ringing of a number of young storks: on 5 June, 13 individuals were provided with a scientific ring. The codes on these rings can be read remotely with a pair of binoculars or a telescope, but the chance that a ringed stork is observed and reported remains rather small. Although such observations teach us a lot, they are still snapshots. With a transmitter, a bird can be tracked continuously, which provides much more information about the survival, the movements and the habitat use of the transmitter-equipped birds.

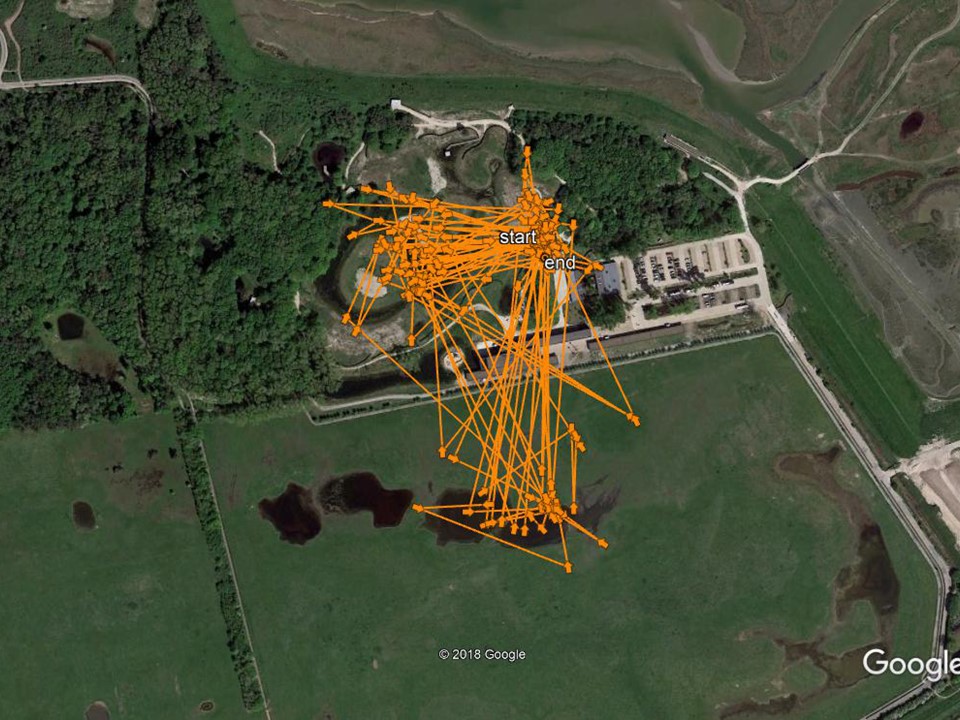

On 26 June, for the first time, three young Zwin storks (from two nests) were equipped with a transmitter. They weigh only 25 grams, which represents less than one percent of the weight of the birds. The transmitters are very sustainable: they operate on solar energy and transmit the data that their GPS collects via the GSM network. Don’t worry if there is no reception: everything is stored in the internal memory and passed on when a signal is available. It is also possible to adjust the transmitter parameters (such as the frequency of location measurements) remotely. The accuracy is astonishing, positions are determined to within a few meters.

Storks on garbage dumps

Before 1990, almost all Western European storks crossed the Strait of Gibraltar (the strait that separates Spain from Morocco) in the autumn to spend the winter in West Africa. Since then, however, much has changed. More and more storks have understood that they could drastically shorten this long and energy-consuming journey by staying in Spain, where they find all the food they need on landfills. In the winter of 2018-2019, up to 46,000 wintering storks were counted on the Iberian Peninsula. This is no less than 20% of the Western European population. These birds also have a higher chance of survival, and return more quickly to the breeding grounds in the spring, where they can occupy the best territories.

But … clouds are rising in the Spanish stork paradise skies! The European Waste Framework Directive prohibits landfills exposed to the open air, and the European Commission took Spain to the European Court of Justice in June 2018, in response to repeated calls for this legislation to be applied in Spain. The Spanish garbage dumps that many storks have learned to use will therefore be closed shortly. This will fundamentally change the state and conditions of their wintering quarters. The RBINS and the Zwin Nature Park are therefore seeking to use the transmitters to help document the impact of this changing situation in Spain on the storks’ migratory behaviour.

The results of the research will be available on a specific project page on the website of the Zwin Natuur Park. It is the intention that more storks will be equipped with a transmitter in the coming years.

As an international airport for birds, the Zwin Nature Park is a knowledge and expertise centre for bird migration. In addition to ringing storks and installing transmitters, the Zwin Nature Park also focuses on ringing of other bird species. From 1 August to 20 October 2019, ringing will take place almost every day, and the public will also be able to gain an insight into this activity. In Belgium, the scientific ringing of birds is coordinated by the BeBIRDS group of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS).

Back to the North !

The first two Bewick’s Swans equipped with a GPS tag during past summer in the tundra of Yamal but at the same site a few days apart, have very recently left their wintering site separated one of the other by … 8000 km!

The first to take the northern route is the adult female 832X. She left Poyang Lake area (southeast China) on 03/03/2016. She had arrived in the region on 25/11/2015 and has successively visited the Sai Hu lakes, Longhu and Longgan lakes. So she stayed a total 99 days near the Yangtze River before resuming her migration back to the north.

Between 03/03/2016 and 07/03/2016, 832X has traveled 1400 km to the north-northeast with a maximum peak of 215 km in 3 hours. Since she is in halt on the Yellow River in the district of Donghan, 250 km from the border with Mongolia. This is exactly where 865X, another Bewick’s Swan from Yamal having wintered in the Yangtze region, had stopped in last autumn migration.

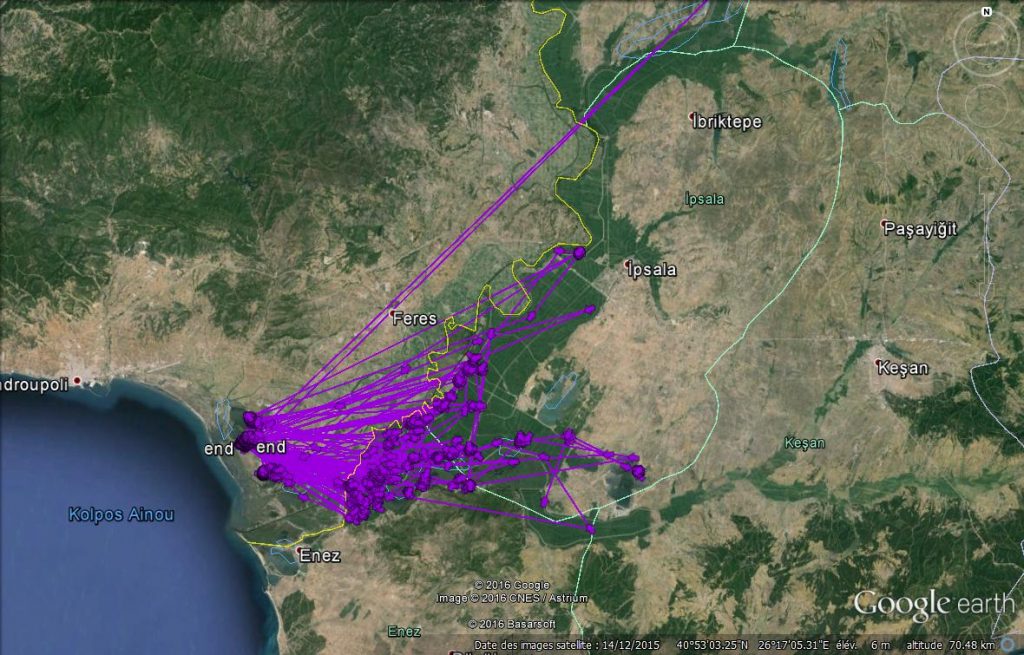

The second Bewick who started the spring migration is 854X. It is a second-winter male that had (after years of questions !) indicated us the route to the Evros Delta. 854X had arrived in the Evros on 12/12/2015.

After 86 days of back and forth between Greece and Turkey, the Evros river making the border between the two countries, 854X flew in the late afternoon of 07/03/2016, heading northeast. In a step of 12 hours of continuous flight and a peak of 265 km traveled in 3 hours, 854X flew over the Black Sea in almost straight line to land on the morning of 08/03/2016 in the Nature Reserve of Chernomorsky, just east of the Bay of Tendra, Ukraine.

Twelve hours later, 854X set off again, this time eastward, for a flight of three hours maximum. At nightfall, he landed at sea, a few km off the Gulf of Khorli, a site where gather in the summer thousands of Mute Swans in flightless moult.

The GPS positions received suggests that during the night, 854X drifted 11 km towards the east. At dawn on 09/03/2016, he took off for a short 90 km flight which led he to the impressive hyper saline lagoons of Sivash, north of Crimea. He stayed there four days and was located several times in cropland area close to water bodies. Most likely he was feeding there.

854X then resumed flight to the east for about 40 km. New stop at night, but this time on Sea of Azov. And new drift during the night, up to 24 km from the coast this time. This morning, 14/03/2016, 854X resumed its journey shortly after 05:00 am (local time) always towards the east. Six hours later he was located 290 km to the east, probably when flying. 854X was then close to Beisug liman where he has stopped 51 days during post-breeding migration 2015, prior to arrive in the Evros Delta. Will he halt there again or will he continue his journey eastward to Russia and Kazakhstan?

To be continued !