In 2021, an article in Nature made world headlines because it equated the carbon released from seabed disturbance due to bottom trawling to the amount of CO2 generated by the global aviation industry. Now these conclusions are refuted by an article also published in the prestigious journal. The authors, including Sebastiaan van de Velde of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and the Université Libre de Bruxelles, fear that using exaggerated figures for bottom trawling will increase global CO2 emissions while reducing global food supply.

An article published today in Nature refutes the conclusions of an earlier paper by Sala et al on the amount of CO2 released from the seabed by bottom trawling. That article made world headlines when it was published in 2021 because it equated the carbon released from disturbance by bottom trawling to the amount of CO2 generated by the global aviation industry.

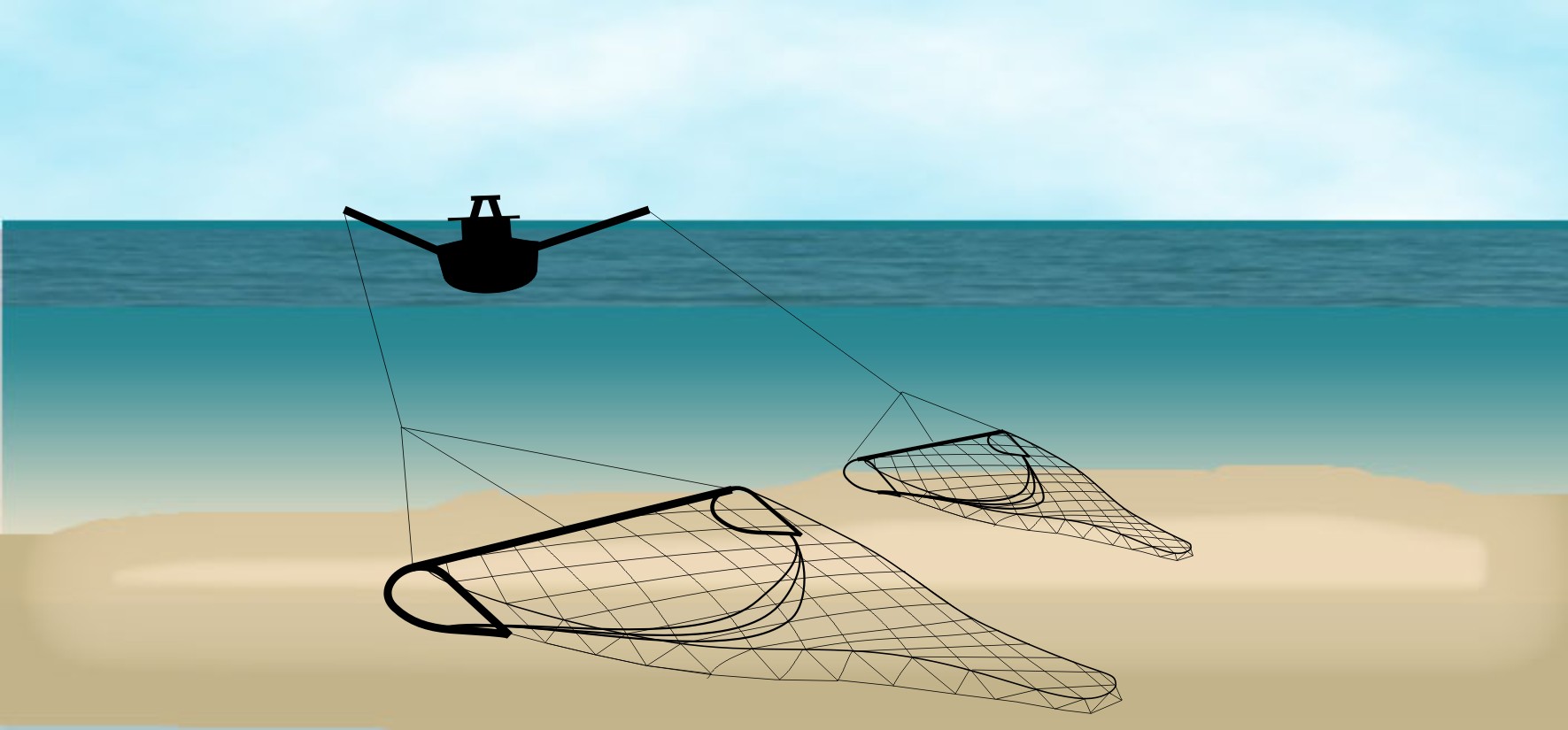

In the new paper, however, researchers show that the methodology used by Sala et al greatly overestimated carbon emissions. To calculate the amount of CO2 released by bottom disturbance from bottom trawling, the authors of the 2021 study modelled the amount of carbon that would be disturbed, assuming that most of this carbon would be converted to CO2.

However, most of the organic carbon in the seabed would decompose and be released as CO2 anyway, regardless of whether it is disturbed by bottom trawling. Only a very small proportion of seabed carbon potentially responds to disturbance by bottom fishing. The effect of bottom trawling on carbon storage in the ocean floor appears to be as much as 100 to 1,000 times smaller than that of global air transport, according to the new study.

“The authors of the original study focused their calculations on the ‘juicy’ and reactive organic carbon at the surface, which would be rapidly released by natural processes anyway, rather than on the aged and much less reactive carbon stored on the seabed,” explains Sebastiaan van de Velde, senior researcher at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and the Université Libre de Bruxelles, and second author of the study. “Since the most reactive carbon is rapidly converted into CO2 anyway, assuming it is affected by bottom trawling greatly inflates the estimated CO2 emissions.”

Unjustly reassured

There is no doubt that bottom trawling disrupts natural carbon fluxes and disturbs marine life on the ocean floor, but seabed carbon fluxes are very complex. The use of exaggerated figures is worrying as many governments and other actors propose to ban bottom trawling and use “carbon credits” to offset other activities. But when the carbon emissions from disturbing the seabed are overestimated by several orders of magnitude, we risk being unduly reassured by any ban on bottom trawling. In reality, this could divert efforts away from more efficient methods, while in the meantime increasing overall carbon emissions while decreasing global food supply.

“Refuting results of previous studies is part of the classical scientific process: one study presents a hypothesis, others challenge it with their own experiments, and that’s how we get closer to the truth,” van de Velde concludes.